The Rector and the Ruined Church

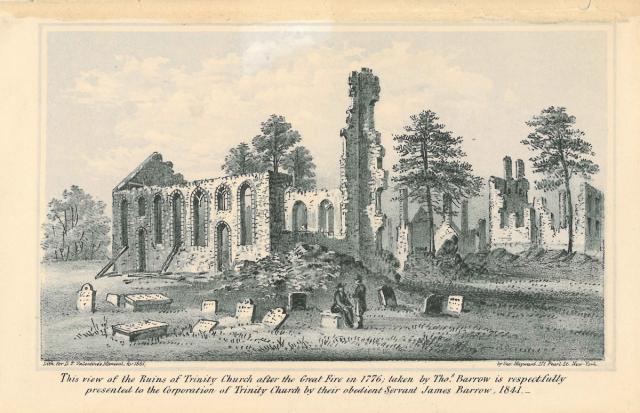

On March 20, 1777, the Rev. Charles Inglis stood among the ruins of Trinity Church and placed his hand on the crumbling, scorched wall. As the vestry looked on, warden Elias Desbrosses instituted Inglis as the fourth rector of Trinity Church, saying, “By Virtue of this Mandate I do Induct you into the Real Actual and Corporal possession of this Church called Trinity Church in the City of New York with all the Rights profits and appurtenances thereto belonging.” Signs of spring surrounded the small group: there were green shoots between the tombstones and birds in the trees, but the city retained a bleak feel. One-third of its buildings had been destroyed in a fire the previous September, and the British Army occupied the city. Patriot prisoners of war were held in deplorable conditions on rotting prison ships in the harbor.

Outside the city in Patriot-controlled territory, Anglican clergy were victimized for their loyalty to the Crown, something they had sworn to at the time of their ordination. Of the 19 Anglican clergy working in New York State, only Samuel Provoost was a Patriot. Fifty-six Anglican clergymen were persecuted during the war: banned from working, their homes destroyed, their families threatened. Four were killed outright.

Trinity parish, inside occupied New York City, was one of the few places in the country where Anglican clergy could practice openly.

Religious life during British occupation continued as normally as possible. Services were held in St. Paul’s Chapel and St. George’s Chapel. St. George’s was also loaned to the Dutch Reformed Congregation, whose church had been seized for use as a prison. The Charity School educated the city’s disadvantaged boys. Forty pounds of beef were delivered to “impoverished widows and housekeepers” at Christmas.

Inglis was sincere in his belief in the British. He published Loyalist essays under the pen name Papinian, including one titled “The True Interest of the American Impartially Stated.” But by 1780, all signs pointed toward a Patriot victory. Necessities were hard to come by in the city, and the vestry was unable to collect rent on church properties. Though Inglis wrote, “The rebellion declines daily and is near its last gasp,” churchmen in other states began planning how to rebuild the denomination in an independent America. At one of these meetings the name Protestant Episcopal Church was chosen. The term episcopal came from a 17th-century English church faction that favored retention of bishops.

On October 19, 1781, General Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, though the British would not evacuate New York City for another two years. Loyalist refugees, both lay and clergy, streamed into the city to await evacuation or acceptance into the new nation.

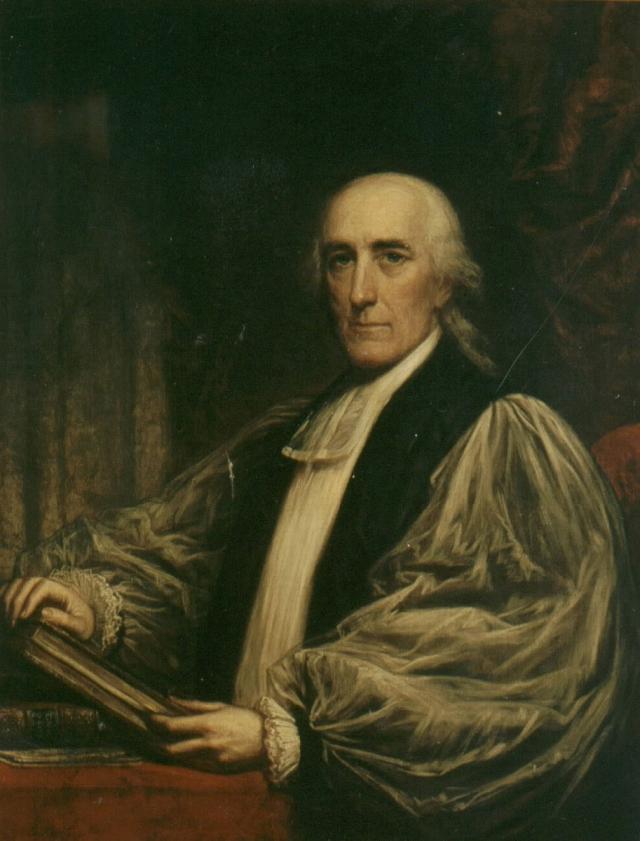

Inglis’s life came apart as the occupation wound down. His eight-year-old son died in January 1782 and his wife soon after. A writ of attainder was issued against him, seizing his property and condemning him to death should he be found in America after British evacuation. (Many states issued these in the aftermath of the war, and most eventually granted Loyalists amnesty. New York did not. The United States Constitution outlawed writs of attainder.) In November 1783, Inglis tendered his resignation and sailed to Canada where he would become the first bishop of Nova Scotia.

After Inglis’s departure, the vestry quickly elected the parish’s assistant minister, the Rev. Benjamin Moore, rector. His installation as rector, however, was blocked. Patriot members of Trinity parish were also returning to the city at this time. They were eager to claim the church as their own. They called themselves “Whig Episcopalians” and included James Duane, the first post-Revolution mayor of the city; R. R. Livingston, who was on the committees that drafted the Declaration of Independence and the New York State Constitution; and John Lawrence, New York City’s representative to the First United States Congress.

But the fate of the Church of England in the new American states was in legal limbo, and the Whig Episcopalians knew it. In places like New York, where the church had been “established,” church property was owned not by local congregations but by the British Crown. The entire legal basis for parish structure, business, and property ownership was void, and state legislatures could legally seize that property. The key to the church’s survival would be obtaining the support and approval of the new legislatures, something that couldn’t be done with Loyalist leadership at the top of the parish.

The Whig Episcopalians called a meeting at Simmons Tavern at Wall and Nassau streets on December 6, 1783. The group concluded that the vestry election and Moore’s subsequent election were illegitimate, given that many parishioners were unable to vote due to the war. Later that week, at the invitation of the Whig Episcopalians, the two groups met at the tavern. No agreement was reached.

Failing in the direct approach, the Whig Episcopalians petitioned the provisional council of the Southern District of New York. Patriot members of the church, the petition said, had fled homes and businesses during the conflict and lost friends in the fighting. “But while your Petitioners acquiesce in these, they cannot consent that Rights to which they are entitled as Members of a Religious Community, should be wrested from them, while they were endeavoring to establish the Civil and Religious Privileges of every Citizen of the State.”

The vestry countered the petition with a radical proposition: abolish the office of rector and replace it with two clergymen with equal power, one from each faction. The Whigs declined the proposition.

The provisional council took action on the Whigs petition in late January 1784, appointing nine trustees to manage the parish estate until further action of the state legislature. The trustees immediately invited Samuel Provoost to return to the city and take leadership of Trinity Church. Moore was ordered to hand over the parish keys, and the vestry resigned en masse shortly thereafter.

On April 17, 1784, the state legislature passed a bill amending Trinity’s charter, fully separating it from the Crown and putting it in compliance with state law. Ownership of the church estate was vested in the corporation itself, and its structures were affirmed, as was its right to pass on property through the chain of rectors, wardens, and vestrymen. A new vestry was elected, and Provoost was officially instituted as the fifth rector of Trinity Church on April 22, 1784.

There’s no doubt: the Whig Episcopalians’ power grab forced Trinity into becoming American, thus preserving the patrimony. There’s also no doubt that the transition cost Trinity earnest and capable leaders and congregants. But not all: after Provoost’s resignation in 1800, Benjamin Moore was again called to the position of rector of Trinity Church, where he served until his death in 1816.