When Seán Dalpiaz came home from prison, he experienced culture shock. Technology had rapidly advanced during his time away; when he saw people taking calls on their Bluetooth headphones, he was taken aback.

“I thought people were talking to themselves. I didn’t know there was something in their ears,” Dalpiaz said. “I didn’t know about text messages. I didn’t know about all that stuff.”

The world had changed and Dalpiaz needed time, space, and support to catch up. Now, as program director of the newly-opened Fulton Community Reentry Center, this is exactly what he hopes to offer the formerly incarcerated men who are heading to the facility this month to begin a new chapter in their lives.

“At Fulton, we welcome and elevate everyone who walks in our doors,” Dalpiaz said. “It’s about helping people meet the world where it is today, versus where they left it when they became incarcerated.”

The Fulton Community Reentry Center officially opened on April 24 as a 140-bed transitional housing facility and comprehensive reentry support center for men over 50 who are returning home from long-term incarceration. The center is a project of the Osborne Association, a Trinity Church grantee that serves individuals, families, and communities impacted by the criminal legal system.

In 2015, New York State handed the Osborne Association the keys to a historic seven-story brick building at 1511 Fulton Avenue in the South Bronx, which once housed a state prison. Osborne envisioned a facility that would serve as more than just temporary housing for people leaving prison. The nonprofit wanted to transform the structure into a place where returning citizens would feel welcomed and safe, where they could learn new skills, and find mentors who would help them adjust to their new lives.

With financial backing from Trinity Church and other funders, Osborne worked with the New York City Department of Social Services to turn this dream into a reality. Trinity has directed over $2 million in grants and investments toward the design and construction of the Fulton Center.

Bea de la Torre, Trinity’s chief philanthropy officer, said she’s proud Trinity played a key role in the extraordinary transformation of this building.

“All New Yorkers deserve access to quality housing, good jobs, and supportive services — and that includes our returning citizens,” de la Torre said. “By radically changing the character and purpose of this historic building, Osborne has given it and its future residents another chance. The Fulton Community Reentry Center is now a symbol of justice, providing dignity and care to people reentering the community, and a potent example of the power of public-private partnerships.”

More broadly, Trinity has made more than $5 million in grants to the Osborne Association since 2018 for programming, services, and advocacy aimed at helping those impacted by the criminal legal system.

Finding stable housing is one of the major challenges people face when they leave prison, according to Dalpiaz. Many people end up in halfway homes, in homeless shelters, or on the street.

“Not having employment, not having family, a lack of resources, lack of skills, that all leads to the lack of housing. That’s the cycle that folks have a hard time getting out of,” he said. “It’s tough. You have to be resilient to get through so many challenges.”

The transition is even more difficult for people who have been incarcerated for long periods of time. Since this is the population the Fulton Center is committed to serving, the Osborne Association took steps to ensure that the space was designed for residents’ comfort — right down to the smallest details.

From the moment they enter the Fulton Center, residents are surrounded by reminders that this is the beginning of a new life. According to Dalpiaz, the color scheme in prisons is limited since administrators don’t want to allow colors on the walls that suggest gang affiliations. As a result, incarcerated people spend years moving between rooms painted dull browns, greens, and grays. But at the Fulton Center, they will be surrounded by bright, vibrant blues, purples, and greens.

Fulton Center security guards use earpieces so that residents won’t have to listen to the crackle of guards talking over walkie-talkies — a sound that is ubiquitous in prisons.

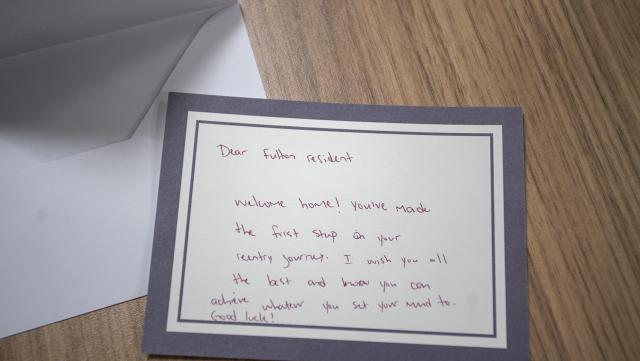

Residents’ living quarters were designed to help them feel at ease. They will come home to welcome baskets filled with items they can use during their stay, such as robes and slippers, as well as handwritten notes from the staff. There’s a large bathroom on each floor, but residents can also access a single full bathroom. The simple act of showering alone — something so many Americans take for granted — gives residents the kind of privacy they couldn’t experience while incarcerated.

There’s a large classroom where residents can attend workshops on entrepreneurship, financial literacy, and conflict resolution. There’s a clothing closet, library, recreation room, and an interfaith meditation room. There’s also a large kitchen that Dalpiaz envisions using as a training ground for residents interested in the restaurant industry.

Building out these new spaces took a gut renovation. The only things remaining from the old correctional facility are the stairwells and the elevators, Dalpiaz said.

“It doesn’t look like any other shelter in New York City, or probably in the country,” he said.

The first residents arrived last week, and the center will likely be full by the end of June. Residents are expected to stay for an average of nine to twelve months, or until they find more permanent stable housing.

The Osborne Association is hoping that by breathing new life into this building, they will also impact the wider South Bronx community. The first floor of the building will host various community group meetings and events, connecting Fulton Center residents to their neighbors and vice versa.

“The community was used to a prison operating there, seeing correctional officers come in and out, seeing folks coming out shackled. That building, I’m sure, caused a lot more harm than it did healing for the people in it and the community around it,” Dalpiaz said. “We’re flipping that reality and giving the men and the building a second, third, fourth chance.”

Plan Your Week at Trinity

Find out what's happening each week at Trinity Church Wall Street: services, special programs, and more.