On New Year's Eve 2019, one million people are expected to fill Times Square to ring in the New Year. Millions more will watch on television as the lighted ball drops down a specially-designed flagpole atop One Times Square at the stroke of midnight, as it has each year since 1907.

But Times Square hasn't always been New York's New Year's tradition. For many years, the city gathered around Trinity Church to hear "the ringing out of the old and ringing in of the New Year" on Trinity's bells.

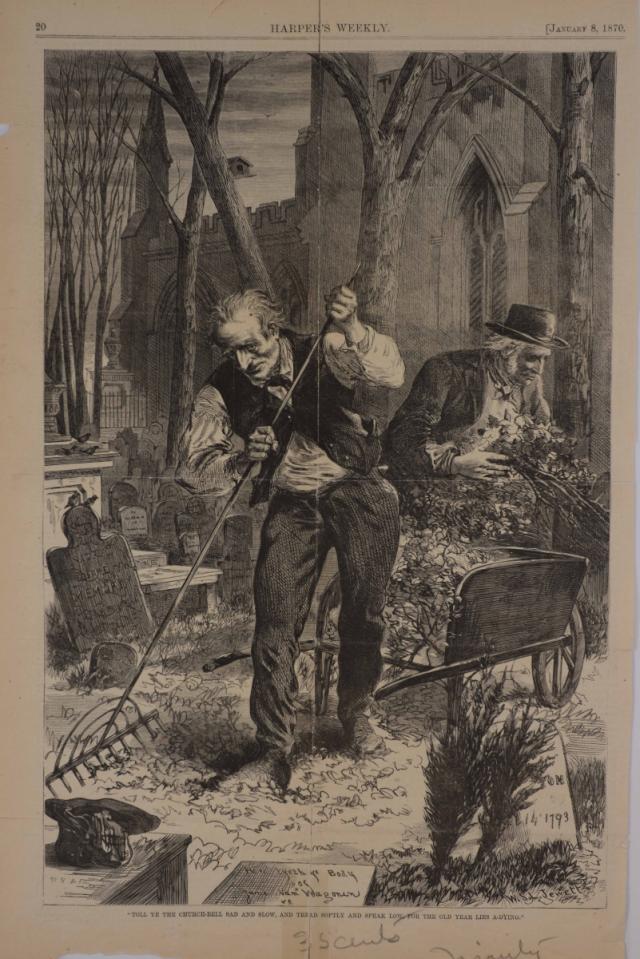

Harper's Weekly New Year's illustration showing Trinity churchyard, 1870

Church bells have long been sounded to mark the New Year. It's possible that the custom in New York began in 1698, when a bell was first installed in Trinity's steeple. The initial reference to the New Year's bell-ringing in Trinity's archives comes from the Vestry minutes of January 12, 1801, when the Vestry resolves "that eight pounds be paid to the Persons who rang the Bells in New Years day." Despite this, the main New Year's custom in New York City in the first half of the nineteenth century remained "calling," a formal reception (and wining and dining) of visitors on New Year's Day.

Crowding into Lower Manhattan to hear Trinity's bells seems to have become a major event around the time the current church building was consecrated in 1846. The new belfry featured a full octave of bells, capable of playing tunes, something James E. Ayliffe, the church's official bell ringer, took full advantage of. The New York Herald described the scene on New Year's Eve, 1860:

There were numerous watchers around and about the venerable walls of old Trinity at the mystic hour "when spirits are said to walk abroad," lingering there to hear the first thrilling peal of the clattering bells in their iron tongued farewell to the dying year. And presently it came. First, the three-quarter chime, giving the world to know that there remained but one-quarter of an hour ere the year 1860 would be drawn into the ever moving stream of ages. And then, as the cold gusts of midnight sighed through the leafless trees and over the graves of the forgotten dead, there floated from the high church tower the stirring music of eight bells chiming in changes and making the air redolent with harmony. This was followed by "Hail Columbia," "Yankee Doodle" and some sweet selections from "La Fille du Regiment."

Fifteen years later, the crowds around Trinity had grown into "an immense throng...completely choking up Broadway for squares away, and extending far down into Wall street," as The New York Times wrote. This was due to both the city's rapid growth and to the efforts of Ayliffe, who planned and executed the popular bell-ringings. Ayliffe was prominent enough at the time of his death to warrant an obituary in The New York Times, which notes that he was born in Gibraltar in 1819 and emigrated to New York in his youth. He seems to have come from a family of musicians, and by 1850 he was working as a musician at Barnum's Museum, across the street from St. Paul's Chapel. He joined Trinity Church around that time, and was appointed bell-ringer in 1855. He also owned "an English chophouse" in Bleecker Street and moonlighted as a violinist. Ayliffe was the man who rang the Trinity bells to signify the end of the Civil War and the transmission of the first telegraph from the United States to England.

Ayliffe was a minor celebrity on New Year's Eve. The January 1, 1878 edition of the New York Times included this behind-the-scenes description of the peal:

A TIMES reporter who visited Trinity steeple at midnight found several ladies and gentlemen seated on the dusty benches, and Mr. Ayliffe, coatless and hatless, played "Happy New-Year to Thee." The nine slender ropes that reaches from nine wooden handles below the bells above each represented a note, and notes were struck by violently pulling down the handles. It was hard and warm work, ringing the bells, and when the tune was finished the perspiration was pouring from the ringers' faces. Seven wax tapers threw a ghostly light over the room, giving just enough light for the ringers to see the notes.

Ayliffe died in October, 1878, of heart disease. He was succeeded by his protégé, Albert Mieslahn.*

The character of the New Year's crowds changed in the 1880s. In 1876, the New York Times described the "thousands of men, women, and children representing all classes of New-York society, from the poorest to the richest, stood quietly enjoying the glorious night and the ringing of the bells," and "joined their voices, and to the accompaniment of the bells sang loudly and impressively the words of the hymn, 'Praise God from whom all blessings flow.'" But by 1885, they reported that crowds "blocked the sidewalks, straggled through the streets, and struggled and pushed each other with all the recklessness of people wholly without intellectual curbs, while the noise they sent up almost drowned the welcome to the New Year which rang out from the Trinity tower." The "horrible din" was largely caused by cheap tin horns.

The Rev. Morgan Dix and children, circa 1880

The crowds grew so problematic that in 1893, the Rev. Dr. Morgan Dix, Trinity's rector, cancelled the peal. Dix, who was sixty-six that year, was more comfortable with the old practice of New Year's calling than he was with boisterous crowds.** On December 28, 1893, he wrote in his diary, "There was the most tremendous question whether the chimes of Trinity are to be rung on New Year's Night. There were 21 reporters at my house and office, all wild about the subject." Noisy crowds gathered around Trinity anyway, and The New York Times reported that some angry "ragamuffins" decided to bring the party to Dix's home on New Year's Eve.

As the Rev. Dr. Dix was about to enter last night in his home, 27 West Twenty-Fifth Street, there came a ring at this door. The servant answered it, and a ragamuffin who stood on the stood thrust in a letter addressed to the Rev. Dr. Dix in a scrawly, boyish hand. Then he ran away. In a few seconds the doctor's ears were greeted by the sounds which seemed to him like the noise of a great consolidated aggregation of sawmills running in unison. He was being serenaded by the boys of the First and Fourth Wards, and thirty of them made things unpleasant for him until his servant, armed with a cane, issued forth and drove the youngsters away.

The following December, under pressure, Dix decided to allow the bell-ringing, but threatened that it would be the final time should "disorder" happen. In a statement, Dix said, "It is a beautiful custom, and no one regretted the necessity that compelled me to have them remain mute more than myself. People were in the habit of assembling in the vicinity of Trinity Church by the thousands. They carried tin horns and made the night hideous with noise, completely drowning the music of the bells. They failed to appreciate the sacredness of the time and forced me to take the step I did. I sincerely trust they will not do so this Monday night. If there is disorder, it will be the last time old Trinity's bells will chime on New Year's Eve."

Apparently the crowds were not too disorderly (possibly because the 400 policemen in attendance seized tin horns), and the custom resumed. Lower Manhattan's New Year festivities reached their peak as 1897 became 1898, and the five boroughs of New York officially merged into one metropolis. In the belfry, Mieslahn played a tune he composed specially for the event, "Farewell, Dear Old New York." Up at City Hall, the flag of the new city was raised beneath a great fireworks display. The New York Times described the scene. "The pyrotechnic display at the City Hall presented a magnificent spectacle from the lower end of Broadway. The mingling of countless colors in the fog-bedimmed atmosphere took on the glory of a gorgeous sunset, and thousands who stood in the rain down by old Trinity viewed the scene from beneath umbrellas."

The custom of gathering at Trinity on New Year's Eve died out in the early twentieth century, supplanted by the Times Square celebration, which began in 1904. Learn more about the history of Times Square New Year's Eve here.

*Mieslahn's 1910 obituary noted that he was "born in the shadow of the old Trinity spire 62 years ago. As a lad he delighted to climb up to the belfry, then the highest point in the district, to help Mr. Ayliffe...From his twelfth year until his retirement last June he climbed the eighty-eight steps to the keyboard more than 10,000 times."

* *In his diaries he notes the spread offered callers to the rectory on New Year's, 1867: baked turkey, pickled oysters, and tongue sandwiches. In fact, Dix never seems to have attended the New Year's bell ringing. On New Year's Eve 1867 he heard Dickens speak at Steinway Hall. The following year he performed a New Year's Eve wedding in the rectory at 9pm. In 1892 he had dinner with friends in his home, and noted "the year passed quietly away."