Big Music, Jewel-Box Space: Welcome to Trinity's Tiny Concerts!

Big Music. A 45-Minute Concert. A 50-Seat Venue.

Don't miss our new Tiny Concert series, performed by members of The Choir of Trinity Wall Street, Trinity Baroque Orchestra, and Avi Stein and Alcee Chriss, organ. Free.

September 17, 2pm and 3pm

Music from 17th century Venice with voices, historical brass and strings

September 18, 6pm and 7pm

Music by Bach and contemporaries with singers and strings

With a new organ, a treasure-chest space, and a brilliantly conceived early music focus, Trinity Church Wall Street is launching Tiny Concerts— a new series celebrating a newly handcrafted pipe organ built principally to play 17th century music, yet still with a broad outlook. In contrast to the rest of the imposing 1846 landmark that presides over Wall Street, everything about these performances will be, well, tiny.

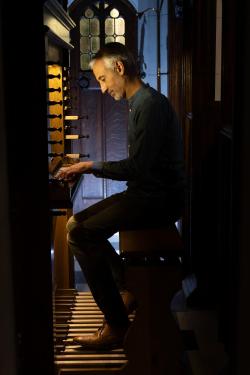

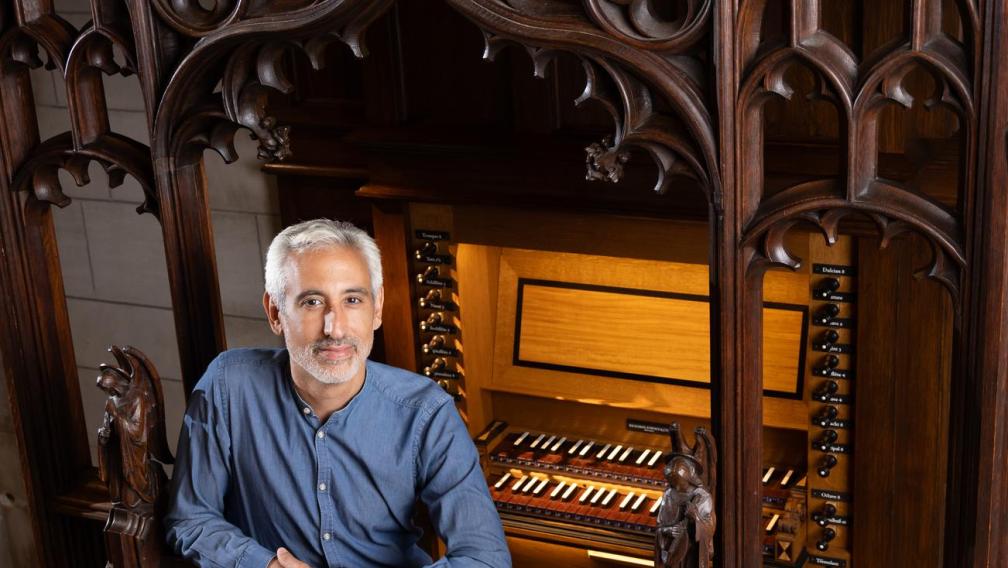

The shows will be just 45-minutes long, and they will take place in the correspondingly mini Chapel of All Saints— a sanctuary tucked off Trinity Church's nave that barely seats 60. “As you walk through the soaring main church and into this jewel box, you feel further and further removed from the canyon of skyscrapers outside,” says Avi Stein, Trinity’s organist. As he puts it, the chapel, added in 1912, is “a buffer from chaotic downtown Manhattan.” The Tiny Concerts promise to further that feeling of remove.

The concert series will launch with shows on September 17 and 18 and pick up again with two shows a month to be scheduled from January through May 2024. Though the events themselves are bite-sized, the building of the organ that will star in these shows was a giant undertaking.

Making Trinity's New Pipe Organ: Medieval Technology in the 21st Century

Seven years ago, the church hired the artisans at Richards, Fowkes & Co., a Chattanooga, Tenn., company, to build a new pipe organ for the Chapel of All Saints. Pipe organs are handmade, so they can take years to complete. Each is necessarily unique as it must suit the size and tenor of its environment. Most pragmatically, that means keyboards, pedals, and pipes—which can often number in the thousands—must all be made to fit into the elaborate, original organ cabinets that were built along with the church. Sometimes the old cabinets are retained, and sometimes they are built new with the organ. “Organs are literally part of a building’s architecture,” explains Stein. “But that means the building is part of the instrument also, and partly responsible for how it will sound.”

With just 50 keys controlling 18 sets of pipes, the chapel's new pipe organ is relatively compact, but these Tiny Concerts are not only about physical size. The organ’s sound has been conceived to match the feeling of the space. To accomplish that, Stein leaned into his own area of expertise: early music. Specifically, he harkened back to the 17th and 18th centuries, a time when the most elaborate instruments were naturally of a smaller scale. “I knew an archaic instrument would not only fit, but also provide a sound that recalls a period that feels as far removed as this little chapel does,” he says. “It is warm, yet exciting.”

Instruments of that era were mechanically controlled, including the connections between the keys and pipes, and so is this one. In fact, the only electronic component of the chapel organ is a motor that drives the air supply. (Until the 20th century, air was hand-pumped.) It all makes for a more earthly sound, or as Stein puts it, a particularly “human” one. “In a larger, soaring room like Trinity, with its vaulted ceiling, the organ looks to the heavens, filling the space in a more grandiose manner, with a multitude of harmonies,” he says. In the Chapel of All Saints, the more direct connection between organist’s fingers and organ’s pipes provides a much simpler intimacy— a feeling only enhanced by the audience’s proximity to the organist. That proximity makes for a particularly intimate listening experience. “Sitting so close means the music just envelopes you,” says Melissa Baker, Trinity’s director of artistic planning. “It’s like a sound hug.”

The closeness will also allow the audience to appreciate the beauty of the instrument even before they hear it. Equal parts art and architecture, the organ is as pleasing to the eye as it is to the ear. Case in point: the dark reddish, deeply grained, and rare Snakewood of the keyboard. And what function exactly does such material provide? Stein smiles as he answers, “It’s just beautiful.” It is no wonder that Richards, Fowkes & Co. calls each one of its handcrafted instruments “an opus.”

The pipes, though attention-grabbing in their own right, serve a more fundamental purpose. Painstakingly cast by hand using a technique that has been in use for over a thousand years, the 1,133 pipes of the All Saints Chapel organ have a high lead content, which, unique among metals, “creates a particularly gentle sound that is perfect for this particular space,” says Stein. The organ also features a rarely heard tuning system, with pure and natural intervals, that was popular in the 17th and 18th centuries and restricts his repertoire to that period (Bach, of course, but also Monteverdi, Gabrielli, and others). But while that has its drawbacks, Stein says, the tradeoff— “a purity and consonant harmony that results in a contemplative and warm sound”— is worth it.

A smaller repertoire for a smaller organ. Tiny Concerts for a tiny space. And yet in the end, the Chapel of All Saints’ new organ has created one huge opportunity. “Because it’s more on the scale of other instruments and voices, the organ mixes beautifully with other musicians,” Stein says. “It’s wonderful to be able to have a musical dialogue that isn’t possible with newer, more orchestral instruments.” In fact, for the first two Tiny Concerts, Stein will perform along with members of The Choir of Trinity Wall Street, accompanied by period instruments played by members of the Trinity Baroque Orchestra. And, as is so often the case, in the Chapel of All Saints, less will definitely be more.